By Grant Tinsley, Ph.D.

I am thrilled to share that my research team just published the results of our study evaluating the accuracy of 14 at-home body fat scales in the British Journal of Nutrition.

While we hope the research article itself will be informative for researchers and practitioners, I also wanted to write this simplified summary of our study, which may be more accessible to many readers.

Before we dive in, here is the link to the journal article on PubMed and the journal website. We paid to make this open access, which means it is freely accessible to everyone. You can also download the accepted version of the article here.

Table of Contents

Big-Picture Summary and Take-Home Messages

If you don’t want to read this whole article, here are the take-home messages up-front:

- We tested 14 at-home body fat scales in this study, alongside one laboratory-grade body fat scale using the same general technology (bioelectrical impedance analysis) and our gold-standard method (the four-compartment model). The outcome we focused on was body fat percentage (i.e., the percentage of your body weight that is fat).

- For each scale, we assessed the reliability (how consistent repeated measurements were), the cross-sectional validity (how close the measurements were to our gold-standard method at a single point in time), and the longitudinal validity (how well the scales detected changes in body fat percentage over time). We considered how accurate the scales were for groups of people and for individual users.

- We ranked the overall performance of each scale, as well as the performance in each of five performance categories.

- For overall performance, the five top-performing body fat scales were:

- Omron HBF-516 ($80). Note: this link is to the HBF-514C, which is identical besides minor software features.

- Tanita BC-568 InnerScan ($220)

- Tanita UM-081 ($49)

- InBody H2ON ($349)

- Withings Body Cardio ($165)

- Most users of at-home body fat scales are primarily interested in tracking their own changes in body composition over time. The five top-performing scales for this purpose were:

- Omron HBF-516 ($80). Note: this link is to the HBF-514C, which is identical besides minor software features.

- Tanita BC-568 InnerScan ($220)

- Tanita UM-081 ($49)

- Withings Body Cardio ($165)

- Tanita BC-554 IronMan ($110)

- Depending on their intended use, some of the at-home body fat scales we tested could be useful for those wanting to assess their body composition.

- Importantly, all body fat scales demonstrated enough error that you should still be cautious when interpreting the results of an individual test, as well as changes detected by the scale over time. If you are using these scales, it would be best to consider their results alongside other metrics (for example, body weight, waist circumference, exercise performance, and mood).

- If these take-home messages didn’t give you all the information you want, keep reading!

Introductory Notes

Before going further, I want to share a few important notes and acknowledgements:

- While all the authors listed on our research article made substantial contributions, the first author, Madelin Siedler, deserves a very special recognition. Madelin, a doctoral candidate in my lab, was responsible for the initial idea of conducting this study and has been involved in all subsequent aspects of the study, including leading the entire data collection, drafting the manuscript, and much more.

- The funds used in this study were my general laboratory funds from Texas Tech University. No company or outside organization financially supported this work in any way, including through donation of materials.

- When possible, the links in this article are Amazon affiliate links. My hope is that, if you find this article informative and choose to purchase an item from Amazon after clicking the links, the commissions will help pay for hosting this website.

- Although they were not involved in this study, I want to disclose that several manufacturers of body composition technologies have either funded research in our lab or loaned or donated equipment to our lab. In terms of bioelectrical impedance companies (i.e., the technology used in at-home body fat scales), we have only received product loans or donations from two companies. These companies include Biospace Inc. (DBA InBody), who loaned us a device for several years, and RJL Systems Inc., who donated a bioimpedance device. One of the body fat scales we tested was produced by InBody, but they had no involvement in any aspect of this study.

How Do Body Fat Scales Work?

All the body fat scales we tested in this study use a technology called bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA).

BIA works by injecting small, imperceptible electrical currents into your body through electrodes that are in contact with your skin. These currents then pass through your body and are received by other electrodes.

Based on what was injected and detected by these electrodes, the scale can estimate the resistance to electrical flow in your body. This information is used within an equation, or series of equations, to estimate body components such as body fluids and body composition.

The reason bioelectrical impedance can be used to estimate body composition is that electrical currents flow more easily through tissues with higher water content, such as muscle, as compared to tissues that have lower water content and higher fat content, such as adipose tissue.

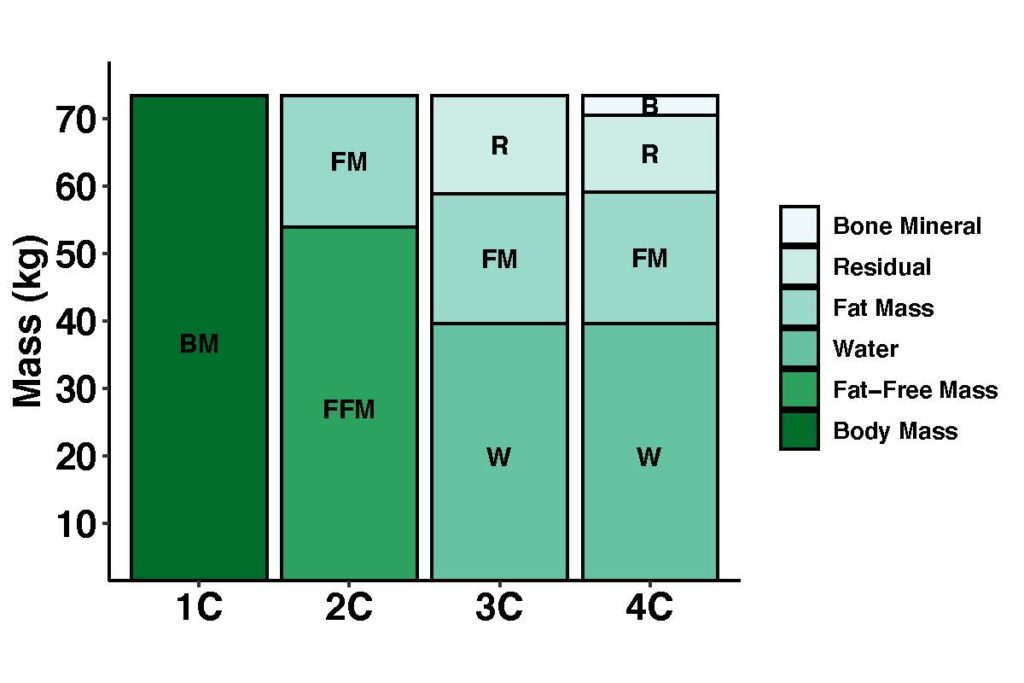

BIA devices use what is known as a two-compartment (2C) model, which means that all of body weight is split into one of two compartments: fat mass and fat-free mass. This also allows for calculation of your body fat percentage (the percentage of your weight that is fat mass).

In most cases, the details of the equations used by specific companies are proprietary, meaning they are not shared publicly. This means that we as consumers typically have no idea how the equations were developed, who developed them, or how valid the procedures were.

This is a big reason why it is important to conduct research like the study being discussed here. Even without knowing the exact equations being used, we can determine how accurate the body fat scales are when used as directed.

Side Note on BIA: BIA technology sometimes gets a pretty bad rap. While there are certainly some BIA devices that perform very poorly, including some in our study, there are others that may be useful in some contexts, when interpreted appropriately. It is also important to note that BIA devices vary widely in their cost, physical form, and complexity. They can range from ~$20 to ~$25,000 USD; use single or multiple frequencies; use electrodes that contact the hands, feet, or both; and use equations that are well-validated or rather poorly constructed.

The Scales We Tested

We included as many popular at-home body fat scales as possible, with a variety of different types and prices represented. Here are the scales we tested:

- RENPHO. $34

- Wyze $40

- WW (Weight Watchers) by Conair $42

- INEVIFIT $40

- Vitagoods Form Fit Currently unavailable.

- Tanita UM-081 $49

- Seca Sensa 804 $90

- Withings Body Cardio $165

- Tanita BC-554 Ironman Elite Series $110

- Omron HBF-516 $80. Note: this link is to the HBF-514C, which is identical besides minor software features.

- Tanita BC-568 InnerScan $220

- Omron HBF-306 $317 (!)

- InBody H20N $349

- HAWANA Currently unavailable

- Seca mBCA 515/514 $11,900 (Laboratory-grade device)

How We Evaluated the Scales

So how exactly did we test these scales?

This section will tell you about the types of performance we assessed, our participants, and how the body fat scales were used. It will also describe the gold-standard method we used for comparison and the primary metrics we used to rank the performance of the scales.

Please note this is a simplified description of our methods. Those wanting all the details should consult the full manuscript.

What Types of Performance Were Assessed?

We assessed the reliability, cross-sectional validity, and longitudinal validity of each scale. What does this actually mean? Let’s break down each of these types of performance:

- Reliability refers to how consistent the results from multiple tests are, particularly when nothing has changed between the two tests. For every participant, we performed two separate back-to-back tests to see how stable the results were. Participants were repositioned between tests.

- Cross-sectional validity. Cross-sectional just means “at a single point in time.” Validity refers to how close the values from the body fat scale were to the values from our gold-standard method (the 4-compartment model). So, the cross-sectional validity can be viewed as how “accurate” a scale is, compared to our best method, at a single point in time.

- Longitudinal validity. Longitudinal validity tells us how similar the changes in body fat detected by the at-home scales over time were, as compared to the changes detected by our gold-standard method.

What Were the Participants Like?

We recruited male and female participants who were generally healthy, between the ages of 18 and 50, and weight stable during the previous month.

For the types of performance that were assessed at a single visit (reliability and cross-sectional validity), we had a sample of 73 adults report to our lab for testing.

Of these participants, 56% were non-Hispanic White, 25% were Hispanic, 14% were Asian, 4% were Black, and 1% were Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.

You can see the basic characteristics of these participants in the table below, with values presented as mean ± standard deviation.

| Age (years) | Height (inches) | Weight (pounds) | Body Fat Percentage | Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | |

| Total sample (n = 73) | 26 ± 7 | 66 ± 4 | 158 ± 37 | 25 ± 9 | 25 ± 5 |

| All males (n = 35) | 27 ± 8 | 68 ± 3 | 176 ± 36 | 21 ± 8 | 27 ± 5 |

| All females (n = 38) | 26 ± 6 | 64 ± 3 | 142 ± 30 | 29 ± 9 | 24 ± 4 |

Of the original 73 adults, 37 participants agreed to return to the lab for an additional visit 12 to 16 weeks later. There were no restrictions on what the participants did during this time.

We expected to see that some participants increased body fat, some decreased body fat, and some did not change. This is exactly what we saw, and this allowed us to assess the longitudinal validity of the devices (how well they tracked changes in body fat over time).

The basic characteristics of the 37 participants completing the second visit were similar to the overall sample, as shown below.

| Age (years) | Height (inches) | Weight (pounds) | Body Fat Percentage | Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | |

| Total sample (n = 37) | 29 ± 8 | 66 ± 3 | 159 ± 34 | 22 ± 8 | 25 ± 4 |

| Males (n = 21) | 30 ± 9 | 68 ± 3 | 177 ± 33 | 20 ± 7 | 27 ± 4 |

| Females (n = 16) | 27 ± 7 | 65 ± 3 | 135 ± 17 | 25 ± 8 | 23 ± 2 |

How Were the Body Fat Scales Used?

Participants came to our laboratory in the morning after a 24-hour period of no vigorous physical activity or exercise, as well as an 8-hour period without eating, drinking, or ingesting other substances.

All tests were performed at the same visit, within the span of about two hours. Each body fat scale was used by the participant as indicated by the manufacturer, under direct researcher supervision.

For the repeated tests, which were used to establish reliability, the participant completely stepped off the scale and was repositioned on the scale for the second test.

The order in which the participants completed the body fat scales was determined by a random number generator.

What “Gold-Standard Technique” Was Used?

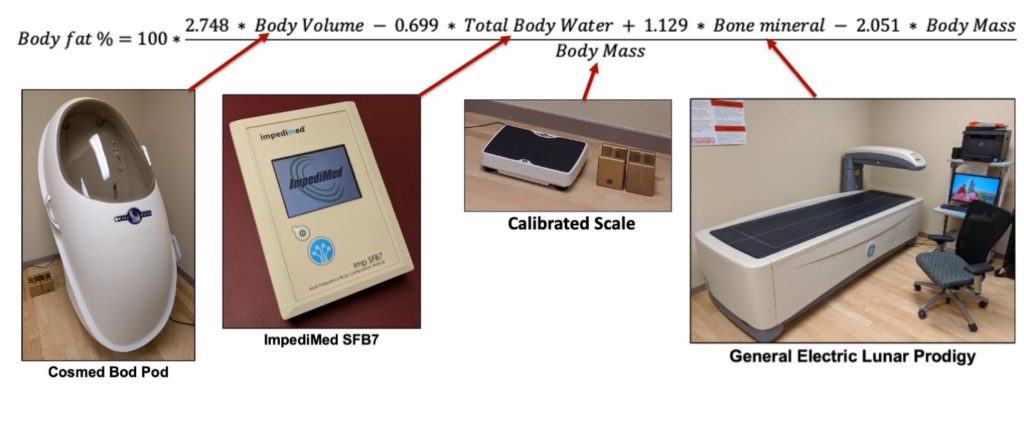

For this study, the “gold-standard” technique we compared the body fat scales to is called the four-compartment (4C) model.

This model separates the body into four compartments: fat, water, bone, and “everything else” (made up of protein, minerals, and stored carbohydrate; this is sometimes called the “residual” compartment).

Since this method takes a greater number of distinct body compartments into account, it is more accurate than simpler models, such as the two-compartment (2C) models used by BIA and other technologies.

To build this model, four separate assessments were performed:

- Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to estimate bone mineral

- Air displacement plethysmography (Bod Pod) to estimate body volume

- Bioimpedance spectroscopy to estimate body water

- Weighing on a calibrated scale to estimate body mass

The variables obtained from each of these techniques are placed into a validated equation to estimate body fat percentage, as shown below.

What Metrics Were Used to Determine Performance?

We used many different metrics to estimate performance of the body fat scales in this study. However, to make the applications clearer, we selected a few of the most important metrics and used them to rank the scales, both in terms of overall performance and performance for certain outcomes (reliability, individual-level tracking, etc.).

While the manuscript has more detail, a general explanation of the three main metrics used in the rankings is included below. For all of these metrics, lower is better since they are reporting the amount of error and we want lower error.

- Precision error (reliability). The precision error is calculated using an equation that includes the variability in the scores of each participant. This essentially means that larger differences between the two tests for each participant results in a higher precision error (worse reliability).

- Total error (group-level validity). The total error can be conceptualized as the average distance of body fat scale values from the line that represents a perfect relationship between the body fat scale and the gold-standard method. This shows, within a group, how far the average individual’s body fat is from perfect agreement with the gold-standard method.

- 95% limits of agreement (individual-level validity). The 95% limits of agreement are one component of a well-established way of comparing two methods, called Bland-Altman analysis. The 95% limits of agreement can be viewed as the range in which 95% of individual differences between methods should fall.

The Results

The journal article provides the gory details of every metric used in our study. However, to make the results more user-friendly, we also provided a table of rankings to indicate the relative performance of each device.

While our rankings make the results much easier to understand, the caveat is that a single metric was used to determine the performance in each of the categories below. So, the ranks are a simplified version of the overall performance.

The table below presents the overall rankings, as well as the rankings in each performance category we evaluated. The scales are listed in order of best overall performance.

| Device | Overall ranking | Overall sum | Cross-sectional Validity (Group Level) | Longitudinal Validity (Group Level) | Cross-Sectional Validity (Individual Level) | Longitudinal Validity (Individual Level) | Reliability |

| Omron HBF-516 | 1 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Tanita BC-568 InnerScan | 2 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 10 |

| Tanita UM-081 | 3 | 22 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Seca mBCA 515/514 | 4 | 24 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| InBody H20N | 5 | 25 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 9 |

| Withings Body Cardio | 6 | 28 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 6 |

| Tanita BC-554 Ironman | 6 | 28 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 1 |

| Omron HBF-306 | 8 | 30 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 7 |

| Wyze Scale | 9 | 44 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 5 |

| INEVIFIT Scale | 10 | 52 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 |

| Seca 804 | 11 | 54 | 15 | 15 | 6 | 15 | 3 |

| Vitagoods Form Fit | 12 | 55 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| RENPHO Scale | 13 | 62 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 |

| Weight Watchers Scale | 13 | 62 | 13 | 11 | 15 | 12 | 11 |

| HAWANA Scale | 15 | 67 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 11 |

If you want a general sense of the actual values that led to these rankings, here are the ranges we observed for each metric (in units of body fat percentage):

- Reliability: precision error ranged from 0* to 0.5%.

- Cross-sectional validity (group-level): total error values ranged from 3.3 to 12.6%.

- Cross-sectional validity (individual-level): 95% limits of agreement ranged from 6.4 to 14.7%.

- Longitudinal validity analysis (group-level): total error for changes in body fat percentage ranged from 1.9 to 2.9%.

- Longitudinal validity analysis (individual-level): 95% limits of agreement for changes in body fat percentage ranged from 3.4 to 5.2%.

The full manuscript includes many figures to visually demonstrate the performance of these methods in greater detail.

*While a full discussion is outside the scope of this short article, there were several devices that appeared to have built-in methods to prohibit body fat values from differing on consecutive assessments. That is, a few devices produced what seemed to be impossibly low precision error values. In our rankings, these devices were subject to a penalty because there was no way to know what their reliability performance truly was.

What Does This Mean For You?

So, what does all this information mean for you?

The answer will depend on your intended purpose for using a body fat scale, your tolerance for error in the values you will get, your budget, and more.

With that said, here are some thoughts that may help you understand and apply the results of our study:

- Some products clearly performed much better than others. So, not all at-home body fat scales should be viewed as equivalent products. These differences are likely due to both hardware and software (i.e., prediction equation) differences.

- Your intended purpose for using a scale may inform your decision of which scale to buy, if any. However, the top three scales in the overall ranking are also the top three for individual-level tracking, which is probably the reason most people use these products. These top three scales are: Omron HBF-516, Tanita BC-568 InnerScan, and Tanita UM-081. Currently, the cost of each scale ranges from $49 to $220.

- All body fat scales, even the top-ranked devices, demonstrated enough error that you should still be cautious when interpreting the results of an individual test, as well as changes detected by the scale over time.

- If you are using any body fat scale, it would be best to consider the results alongside other metrics (for example, body weight, waist circumference, exercise performance, and mood). Using multiple metrics can help you get a better sense of how your body is really changing over time. I would not use an at-home body fat scale as your only way of quantifying how your body is changing.

- With the caveats above, I think the performance of the top-ranked scales was good enough that it is reasonable to use one of these as part of your health tracking program. Over time, you may find that the scale helps you track progress. Or, you may decide it doesn’t really help you all that much.

Closing Thoughts

I hope you have enjoyed learning more about our research team’s study on the performance of popular at-home body fat scales.

We had a lot of fun conducting this study, and my research team – particularly Madelin Siedler – deserves much recognition for their hard work on this project.

If you didn’t get all the information you want here, please feel free to read the full research article. If you can’t access the article, just send me your email address in an Instagram message, and I can provide the article for your personal use.

If you want to stay caught up with our lab team’s research, I regularly share updates on Instagram.

Thanks for reading, and I hope this information helps you make informed decisions about which at-home body fat scale to use, if any!